It’s been a decade or two since I technically should have outgrown them, but I love Disney movies. I still know all the songs. I still have my favorite characters. And I don’t think I’m alone: Everyone has his or her own answer to “what’s your favorite Disney movie”—and most of us are unashamed to admit it.

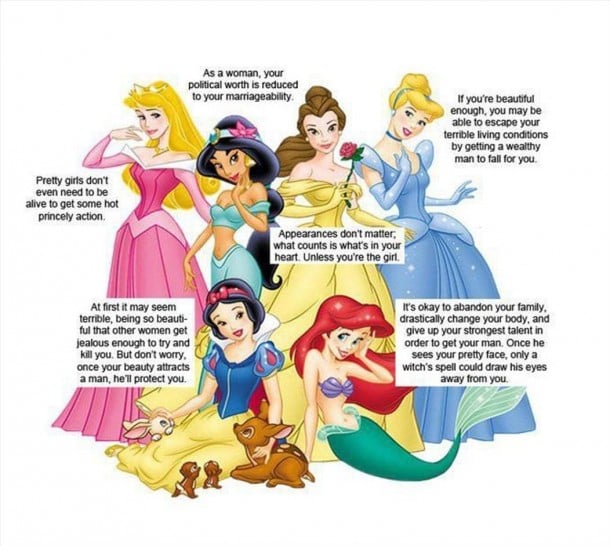

So what do you learn from Disney movies? This picture—that’s recently been circulating the web—promotes one idea: Be beautiful. I have to admit I felt a little sad seeing it, because I detect some uncomfortable truth in those captions next to the characters I automatically want to defend.

These princesses do have other, more substantive qualities besides beauty. They are selfless, they are loving, they are smart. But often it is the viewer—not the prince—who sees these qualities and gets to know these kick-ass women. To the prince, the princess starts off—and, in many cases, remains—just a pretty face.

I wonder if the stories would turn out the same way if their heroines were more flawed. Would Cinderella be rewarded if she lost her temper? Would Snow White be saved if she were not so fragilely feminine? If Belle is so smart and good, why must she be beautiful? “Average-looking and the Beast” is a less catchy title, certainly, but would Belle’s love story be the same were she less physically appealing?

Maybe it would. Maybe the princes do love the princesses in the way the viewers do. The more recent movies portray more balanced relationships: the Beast comes to love Belle for her heart and her brain, and Aladdin and Jasmine become rebellious pals (after Aladdin first sees Jasmine’s almond eyes and sexy two-piece, that is). But in many tales, we don’t know if the beauty the Prince beholds is more than skin-deep, because the princess has taken her self-realizing journey in the privacy of her own home, with her animal or fairy friends (seriously, princesses, where are your human friends?)—and it has often excluded her prince.

The filmmakers did not write the classics. They did not concoct these age-old tales. But in the artistic rule-bending that comes with interpreting a story, I wish we could see a heroine who is more “real” looking, who is more flawed, and whose sense of fulfillment extends past her wedding day. And in a story that applies to all modern girl-viewers, I wish the love between a prince and a princess could be equal, mutually saving, and strong—even in the face of imperfection.